This sermon reflection explores two visual concepts to help us think about choosing to name others as enemies or as neighbours.

I preached it at Wesley Church in Wellington, New Zealand on 11 Sept. 2016, the 15th anniversary of 9/11.

I welcome your feedback to me at: books@pgpl.co.nz

The full text of the reflection is shown below after the video.

Reflection: Who is my enemy?

Let’s pray: May the words of my mouth and the meditations of all our hearts, be acceptable to you, O God, Amen.

Jesus parables were always challenging and in that style I have titled this reflection: “Who is my Enemy?”

The ideal of loving God and loving your neighbour was not new in Jesus’ time. In Leviticus 19:18 we are told “Don’t seek revenge or carry a grudge against any of your people. Love your neighbour as yourself.” The ten commandments given to Moses are rules about living harmoniously in community with our neighbours. So these ideas had been part of the Jewish tradition for many centuries before Jesus.

In Matthew chapter 5 we find Jesus sharpening, making more provocative and demanding, the commandments in the Old Testament. There are a series of teachings in the pattern: “You have heard that it was said…But I say…” For instance:

You have heard that it was said to those of ancient times, “You shall not murder”; and “whoever murders shall be liable to judgement.” But I say to you that if you are angry with a brother or sister, you will be liable to judgement;”

And…

You have heard that it was said, “An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.” But I say to you, Do not resist an evildoer. But if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn the other also; and if anyone wants to sue you and take your coat, give your cloak as well; and if anyone forces you to go one mile, go also the second mile.

And…

You have heard that it was said, “You shall love your neighbour and hate your enemy.” But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven; for he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the righteous and on the unrighteous.

Jesus adds to the commandments to love God and neighbour, the challenge to also love your enemies.

Here is a paradox: If you can learn to love your enemy, can they still be your enemy?

Two things have brought this question into focus for me.

I have been reading Jewish academic Amy-Jill Levine’s book “Short Stories by Jesus: The enigmatic Parables of a controversial Rabbi.” She has lots of stimulating ideas about how to interpret Jesus’ parables, as they have come down to us in the Gospels, in modern translations of the Bible. In her comments on the Good Samaritan story, in which the lawyer asks, Who is my neighbour, Levine says something remarkable.

It relates to how Hebrew is written down. In the formal written Hebrew used in handwritten scrolls of scripture, only the consonants are printed. The person reading the text has to mentally add in the appropriate vowels, based on the context of the rest of the sentence.

Let me demonstrate in English with the consonants T L L.

We can form many words by adding vowels to these letters. The context will help us, for example:

“A child is short, but an adult is…. TALL.”

“Ask me no questions, TELL me no lies”

“The shopkeeper put the money in the TILL”

“She paid a TOLL to cross the bridge.”

“And for fans of early 1970s folk rock, we have the band Jethro TULL.”

You get the idea.

Back to Amy-Jill Levine.

In Hebrew, the words “neighbour” and “evil” share the same consonants (Resh ר Ayin ע); they differ only in the vowels. Both words are written identically. ע ר

So on the page these two consonants can stand for two opposite ideas.

Combined with Hebrew vowels this way, the resulting word means

רֵעַ שֵם

friend, comrade, buddy, colleague ; neighbour, another

Or combined with vowels this way, the resulting word means

רַע שֵם ז’

bad, evil ; villain ; trouble, ill

(Sorry I can’t pronounce the Hebrew words.) But can you see the challenge here?

You or I reading the text have to decide whether it means enemy or neighbour based on the context. The meaning is not fixed, but flexible.

Taking this idea one step further, if we can choose to interpret the same text two different ways, can we also choose whether to consider another person as a neighbour or an enemy? I think we can.

Today is the 15th anniversary of the event that Americans call 9/11. After the twin towers of the World Trade Centre in New York were destroyed, people in the United States flew flags from their houses and many started going back to church again. In the face of an identifiable enemy and threat, they united behind traditional symbols of meaning and togetherness.

The government response was to seek revenge by going to war in Afghanistan and Iraq. Horrifying wars, which have led directly to many of the conflicts we see today in the Middle East. The prophesy from Jeremiah we heard this morning brings to mind the devastation to people, and to the land itself, that war causes. It is a warning to follow the ideals of loving God and neighbour, or face catastrophe.

Many odd things happened on 9/11. There is a lot of speculation about what really happened and why?

What is clear is that people in the United States identified themselves as us the good guys under attack from them, the enemy.

That’s where the trouble starts, by identifying and naming someone else as different, as other, rather than looking for the things we have in common.

How can we discover what we have in common with another person?

I find social occasions with lots of people making small talk very difficult. What works for me is to find one person to talk to and by listening carefully to what they are saying, find a topic that is important to them to talk about. Then I can contribute my ideas and experiences and we get to know each other a little.

The second thing I want to share with you is a visual idea I have been mulling over since February.

Religious beliefs can divide or unite people.

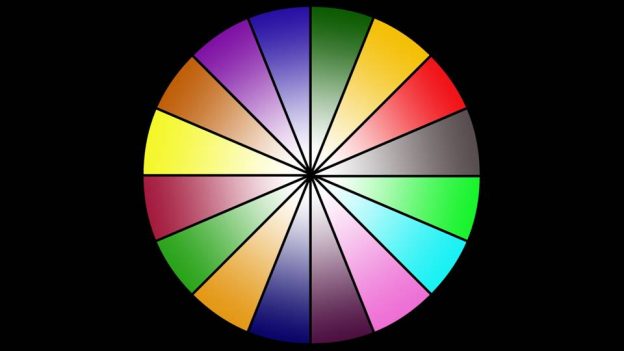

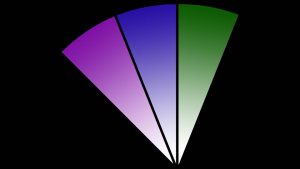

Imagine for a moment that this segment represents Methodists. The darker shades at the top of the segment are where we find the sacred texts, rituals and traditions that we hold onto most firmly. John Wesley’s sermons, Charles Wesley’s hymns, an open communion table and a concern for social justice. These are things which Methodists identify with.

Imagine for a moment that this segment represents Methodists. The darker shades at the top of the segment are where we find the sacred texts, rituals and traditions that we hold onto most firmly. John Wesley’s sermons, Charles Wesley’s hymns, an open communion table and a concern for social justice. These are things which Methodists identify with.

Lets say that the next segment represents Catholics. The darker shades at the top of the segment represent devotion to the Pope, rosary beads, regular confession – the things that Catholics hold dear.

Lets say that the next segment represents Catholics. The darker shades at the top of the segment represent devotion to the Pope, rosary beads, regular confession – the things that Catholics hold dear.

Lets say the next segment represents Islamic faith. The darker shades towards the outside of the segment represent a belief in the prophet Mohammed, the Koran, pilgrimage to Mecca and the other things that Moslems hold dear.

Lets say the next segment represents Islamic faith. The darker shades towards the outside of the segment represent a belief in the prophet Mohammed, the Koran, pilgrimage to Mecca and the other things that Moslems hold dear.

Now lets complete the circle with other faiths.

Now lets complete the circle with other faiths.

Note the black lines separating the segments. They symbolise the divisions between people of faith. These divisions can lead to intolerance and conflict. Taken to extremes they can lead to violence and war. I imagine this as a journey into the darkness, which swallows up all the good things about faith and leads to oblivion.

[Show slides of circle receding into blackness]

What if instead we look inwards to the centre of the wheel, towards those things which we have in common with other people and other faiths. And let’s remove the borders between us. Now as we journey towards the light at the centre, we are free to sample the ideas and ideals of other faiths and discover the things we have in common.

What if instead we look inwards to the centre of the wheel, towards those things which we have in common with other people and other faiths. And let’s remove the borders between us. Now as we journey towards the light at the centre, we are free to sample the ideas and ideals of other faiths and discover the things we have in common.

Loving God (or Gods) and loving neighbour are universal ideas, shared by people of faith.

[Show video of turning circle]

And what if the Holy Spirit blows and the circle rotates, pivoting around the light in the centre and blurring the distinctions between us?

Is world peace really that easy? No, but Jesus pointed us in the right direction.

In the Good Samaritan story the lawyer wants an easy, tick the box answer to eternal life. Instead Jesus tells him to love his neighbour, a lifelong commitment. So the lawyer asks, OK who is my neighbour? and gets an unpalatable answer. Your enemy, the Samaritan, is your neighbour too.

Jesus’ wisdom that we should love our enemy still challenges us profoundly today.

If you can learn to love your enemy, can they still be your enemy?

No, because of your change of heart, they are now your neighbour.

Amen.