The following review by Jione Havea — Senior lecturer in biblical studies at the United Theological College & School of Theology, Charles Sturt University — will appear in the August 2015 issue of the Uniting Church Studies journal.

Rev Havea is a Tongan Methodist minister and is the Principal Researcher with the Public and Contextual Theology Research Centre.

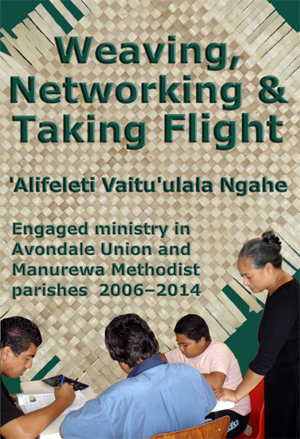

Weaving, Networking & Taking Flight

‘Alifeleti Vaitu’ulala Ngahe

(Wellington, Philip Garside Publishing Ltd., 2014),

pp. 68. ISBN 9781501004476 (pbk).

“This slim book is rich with stories, metaphors and invitations for ministering across cultures, generations and languages, written by a Methodist Minister in Aotearoa New Zealand. Ngahe reflects on his ministry over nine years at two parishes (Avondale and Manurewa) and identifies stepping stones for those who wish to be involved in what he calls “engaged ministry,” which simply means to be not just saying it, but doing it (p. 11).

Ngahe values the practice of reflecting on one’s experience and ministry, and then sharing the wisdom gained with other colleagues and other ministry agents. Those are the motivations for Ngahe’s work and I hope that this book will inspire other Pacific islanders to reflect and share, instead of hiding, their experiences, stories and wisdom. This hope echoes a biblical opinion: that the lamp which is not lit and placed on the table is of no use to anyone.

Ngahe developed his reflection according to three metaphors borrowed from the life practices of three different subjects: weaving of mats by Tongans, spinning of webs by spiders and the flight of birds. On first view, these metaphors could be unpacked toward defining forms of ecological ministry. Maybe that is a task for another series of reflections! At a deeper level, the metaphor from Tongan mat-weaving represents Ngahe himself, and his place in the two parishes, represented by the other two metaphors. Ngahe is a Tongan weaver who “net-works” with a spinning spider (hence the word “networking” on the title of the book) representing Avondale, and a bird in flight representing Manurewa (a name that consists of two Māori words: manu translates as bird, and rewa translates as kite).

The first metaphor is weaving. Weaving is a communal activity in Tonga, and the outcomes are various kinds of mats for different persons and for different purposes. Mats are made of the interweaving of strands and at the end, the edges are unfinished. “They remain open and ready for more strands to be woven in” (p. 14). This is how Ngahe saw his ministry at Avondale. A mat was already being woven, when he arrived. That mat was unfinished. He wove more strands into that mat; then it was time for him to move on, leaving the mat for the next minister and the community to add more strands. In this regard, ministry is never finished off. One comes to the mat (read: ministry), adds a few strands, then leaves the edges unfinished for others to join in the weaving.

The second metaphor comes from the Avondale Spider, which is an icon at the Avondale Town Centre. Ngahe reflects on the process and art of spinning a web. The hardest part is the first thread, and finding an anchoring point for the web. Once that’s in place, then the spider goes back and forth to weave its intricate web. For Ngahe, the spider is in a process of net-working. This is valuable insight for engaged ministry: get the first strand anchored then net-work with other churches, other organisations, and other social bodies, to cooperate in building the web (read: community).

The third metaphor, bird in flight, is inspired by the name of Ngahe’s second parish: Manurewa. Similar to the spider, the bird has to struggle to get off the ground as it starts its flight. But once it is in the air it floats, almost effortlessly, like a rewa (kite) that is being carried by the wind. Mission is like this also. It needs a lot of help to start its flight, but once it is in the air, it will glide almost effortlessly. This is how Ngahe experienced his ministry at Manurewa, where the support of the community made the mission of the church almost effortless. Almost!

One of the strengths of this book is the way Ngahe explains the three metaphors with stories of his ministry, which was always engaging the community in different mission projects, including working on a car park mural at Manurewa. For Ngahe, mission is about hospitality, compassion, empowerment and hope (pp. 42-43).

The chapter on theological themes is worth reading and reflecting upon (chp 5). Ngahe invites further reflection and engagement around the theologies of hospitality, which requires breaking down the barriers that come with social status, and transformation, which needs to be at the physical also and not just in a spiritual exercise. Ngahe closed the book with his ten personal (chp 6) and ministry (chp 7) learnings, which reads like a “top ten list” (à la David Letterman) instead of a list of “ten commandments.” Personal and the ministerial experiences are indeed interwoven, and reflection on one leads to reflection on the other.

I commend this book not just for Tongan Methodist Ministers but also for all ministry agents who are involved in intercultural and engaged ministries. Who isn’t? In other words, this book is for you as well!

I hope for two kinds of responses to Ngahe’s work: First, for readers to critically engage his proposals. Do the metaphors work? I’m conscious that some are scared of spiders, for instance, while others eat them as a snack. What other metaphors would you weave into Ngahe’s mat? Second, I hope that this work will inspire Pacific Islanders to reflect on your ministries, write your stories, and share your wisdom with the rest of us. If you don’t, then future generations of Pacific Island ministers will have to learn from non-Pacific Islanders. You may of course write in your Pacific languages. In other words, you don’t need to write in English. But writing in English is also an opportunity for non-islanders to learn from the rest of us.

Finally, I look forward to the outcome of the next nine years of Ngahe’s ministry and for his further sharing of his reflections and his gifts.”